Powering On Your Linux System: The Linux Boot Process

An image of the Linux terminal, executing a command that requires “sudo” level permissions.

When you press the power button on a modern computer, a well-orchestrated series of events begins. From tiny firmware routines preserved in non-volatile memory to complex user-space services that prepare your desktop, booting up a systems is a layered process that spans hardware initialization, firmware decisions, kernel responsibilities, and user-space setup. Understanding these layers helps engineers, system administrators, and curious users troubleshoot boot problems, optimize start-up times, and design robust systems. In this post we’ll walk through a series of steps, which highlights what really happens from power-on to login, expanding each stage into the details and mechanisms that make a reliable boot possible.

Power On and Firmware: POST and Initialization

When you turn on a machine, the first software to run is not the operating system but firmware stored in non-volatile memory on the motherboard. Historically, this firmware was the Basic Input/Output System (BIOS). On modern machines it is often Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI), which supersedes legacy BIOS with a richer, modular interface, faster boot paths, and support for larger disks and secure boot features.

The firmware’s immediate job is to execute a Power-On Self Test (POST). POST is a collection of diagnostic checks the firmware performs to verify critical hardware components are present and functioning. Typical POST actions include:

Basic CPU initialization and setting the processor into a defined state.

Checking and detecting installed memory modules (RAM), testing for basic accessibility.

Detecting the presence of essential chipset components and timers.

Initializing chipset controllers, such as system timers and interrupt controllers.

Detecting and initializing primary buses (PCIe, SATA controllers, NVMe controllers).

Verifying the keyboard controller or other essential input devices (legacy behavior—many systems now treat this less strictly).

Early video initialization so firmware can present visual messages and menus.

POST may produce audible beeps or on-screen messages if it encounters problems. In early boot stages, before the OS can run device drivers, POST acts as the only broad self-test environment, allowing hardware issues to be identified before attempting to load software that relies on that hardware.

UEFI expands on the capability of legacy BIOS by offering a device driver model, a richer runtime environment, modular drivers for different device classes, and boot services. UEFI can read filesystems directly (such as FAT-formatted EFI system partitions) so it can locate bootloader applications by file path rather than relying solely on a fixed sector on disk. Secure Boot, an optional UEFI feature, verifies cryptographic signatures of bootloader and OS components to mitigate unauthorized code execution during startup.

Device Discovery: Understanding the Platform

Once POST completes and the firmware moves from raw hardware checks into configuration and device enumeration, it detects devices connected to the system. Device discovery is critical: the firmware must determine what the machine contains and present enough information to subsequent stages to allow them to initialize and use hardware correctly.

Key elements detected by the firmware include:

CPU: The number of cores, supported features (such as virtualization extensions, instruction set capabilities), and microcode level. Some firmware will load an initial microcode update into the CPU as part of early init.

Memory (RAM): Size, number of modules, and sometimes basic memory training is performed to ensure DIMMs operate at correct timings and voltage.

Storage devices: SATA, NVMe, and other block devices are enumerated. UEFI’s ability to read filesystem metadata enables it to locate bootloaders within an EFI System Partition.

Peripheral buses and cards: PCIe devices, including GPUs, network interface cards, and expansion cards, are listed and optionally initialized to a level where basic functionality works.

Input/output controllers: USB controllers and keyboards, serial console options, and any other legacy interfaces.

The firmware also constructs and exposes boot environment tables that describe hardware to the OS. For example, UEFI exposes configuration tables and runtime services, and provides a predictable device path model that bootloaders and the kernel can use to locate hardware. On systems that rely on network boot, firmware can offer Preboot Execution Environment (PXE) support to fetch boot software from a network server.

Boot Device Selection: Where Does the OS Live?

After detecting hardware and preparing basic services, the firmware must choose a device to boot from. Boot device selection can be influenced by user settings in the firmware configuration (the “boot order”), automatic fallback logic, or explicit selection at boot time via a boot menu.

Common Boot Sources Include:

Local storage: Hard drives or SSDs (SATA or NVMe). With legacy BIOS, the firmware looks for a Master Boot Record (MBR) containing a bootloader in a fixed location. With UEFI, the firmware reads an EFI System Partition and launches a bootloader application (for example, a vendor boot manager or GRUB’s EFI binary).

Optical media: CD or DVD ROMs are other optional sources.

Execution: The Systemd Service

Once the kernel has initialized hardware drivers and mounted the root filesystem, control is handed to the init system (such as systemd, SysV init, or an alternative), which orchestrates the remainder of the boot. The init system first parses its configuration files and unit definitions to determine the desired system state and dependencies. It brings up essential background services in an order that respects those dependencies: udev populates and manages device nodes as hardware is enumerated, networking services configure interfaces and bring up links, and logging services capture kernel and early user-space messages for later troubleshooting. The init system also evaluates and activates system targets or runlevels that represent high-level states (for example, multi-user, graphical, or rescue), ensuring system services required for those targets are started.

Target Run: Running .target files and Startup Scripts

When the system target that provides interactive access is reached, the init system starts login agents: for text-mode operation it spawns getty processes on configured virtual terminals to present login prompts; for graphical operation it starts a display manager (such as GDM, LightDM, or SDDM) which initializes the X11/Wayland server and shows a graphical login screen.

Common Components in this step:

.target files (systemd):

Purpose: .target units in systemd group and order related units; they represent synchronization points (milestones) such as multi-user.target (text-mode multiuser) or graphical.target (multiuser plus graphical session).

Unit relationships: Targets pull in other units via Wants=, Requires=, Before= and After= directives. When a target is reached systemd attempts to activate every unit it Wants/Requires, observing ordering constraints.

Activation logic: systemctl isolate or default.target symlink controls which target is active. When switching, systemd stops units not wanted by the new target and starts the units the target pulls in, using parallel activation where possible.

Files and locations: unit files live under /usr/lib/systemd/system, /etc/systemd/system, and runtime units in /run/systemd/system. Targets are plain text unit files with Type= not used; they primarily list dependencies.

Masking and overrides: Admins can mask a unit (prevent activation) or add drop-in overrides in /etc/systemd/system/.d/ to change dependencies/ordering without editing packaged files.

Startup scripts and sysv compatibility:

SysV init scripts: Systems may still run legacy /etc/init.d scripts via systemd-sysv-generator which creates transient units from scripts at boot. These scripts use LSB headers (### BEGIN INIT INFO) to express dependencies and runlevels.

Exec sequence: Start scripts execute commands that set up services (daemons), create device nodes, mount filesystems, configure kernel parameters (sysctl), or start listeners.

Ordering and parallelism: systemd converts script headers to dependencies; however, long-running or blocking init scripts should use proper Type= settings in native units to avoid stalling boot.

Display manager and graphical login (GDM, LightDM, SDDM):

Role: A display manager is a system service that starts the graphical server (X.Org or Wayland compositor), presents a login greeter, authenticates the user, and launches the user’s desktop session.

Server initialization:

X11: The display manager starts X.Org server with appropriate driver modules (DRI, Mesa, kernel modesetting via KMS). It configures display outputs, screen resolution, and input devices through xorg.conf snippets or automatic probing. X11 runs as a separate process (Xorg) and manages DISPLAY=:0.

Wayland: For Wayland compositors (GNOME/Wayland, SDDM with Wayland support), the compositor itself is the display server and may run directly as the DM child; it manages buffers via DRM and libwayland, and uses Mesa EGL for rendering.

User Experience: Authentication is Key

After a user authenticates, the login manager or PAM stack sets up the user session environment, applying system-wide and user-specific environment variables, resource limits, and session hooks. Following authentication, user session services and the chosen shell or desktop environment are launched. These components load user-specific settings (dotfiles, GNOME/KDE configuration, autostart entries).

Getty processes (text-mode login):

Role: getty opens a tty (virtual terminal) device (e.g., /dev/tty1), configures serial/terminal line settings (baud, echo, line discipline), and presents a login prompt. When a user logs in, getty execs a login program (agetty, mingetty, or util-linux getty) which then invokes /bin/login to authenticate and set up the user session.

Configuration: getty instances are typically managed by getty@.service template units in systemd. They are instantiated per terminal (getty@tty1.service). Template parameters control the device, baud rate, and autologin options.

Terminal handling: getty performs termios configuration (setting ECHO, ICANON, input/output speeds), optionally sets environment variables (TERM), and ensures correct ownership and permissions on the TTY device node.

PAM and authentication: /bin/login uses PAM modules for authentication, account/session management, and can execute pam_motd, pam_limits, pam_env to provide messages, resource limits, and environment setup.

Seat and device management: Display managers interact with logind (systemd-logind) to acquire seats and device access (VT switching, DRM devices, input devices) and to manage permissions using udev policy and D-Bus. logind provides session tracking, power key handling, and device ACLs.

Greeter and authentication: The greeter runs as an unprivileged process or within the DM process and communicates with the display manager core. Authenticationtart per-session background processes (tray agents, clipboard managers, file-indexing daemons). System-wide services continue running in parallel: long-lived daemons, scheduled task runners (cron, systemd timers), and other infrastructure processes provide networking, storage, and application support.

At this point the machine has reached its normal operational state: services are active, device nodes are available, users can run applications, and system monitoring and logging are ongoing. The init system stays resident to supervise services, restart failed units according to configured policies, and manage dependencies for unit changes. When a shutdown or reboot is requested, the init system executes an orderly teardown: it stops services in the reverse order of startup (honoring dependencies), unmounts filesystems, synchronizes pending I/O, and instructs the kernel to power off or reboot, ensuring a clean transition and minimizing risk of data loss.

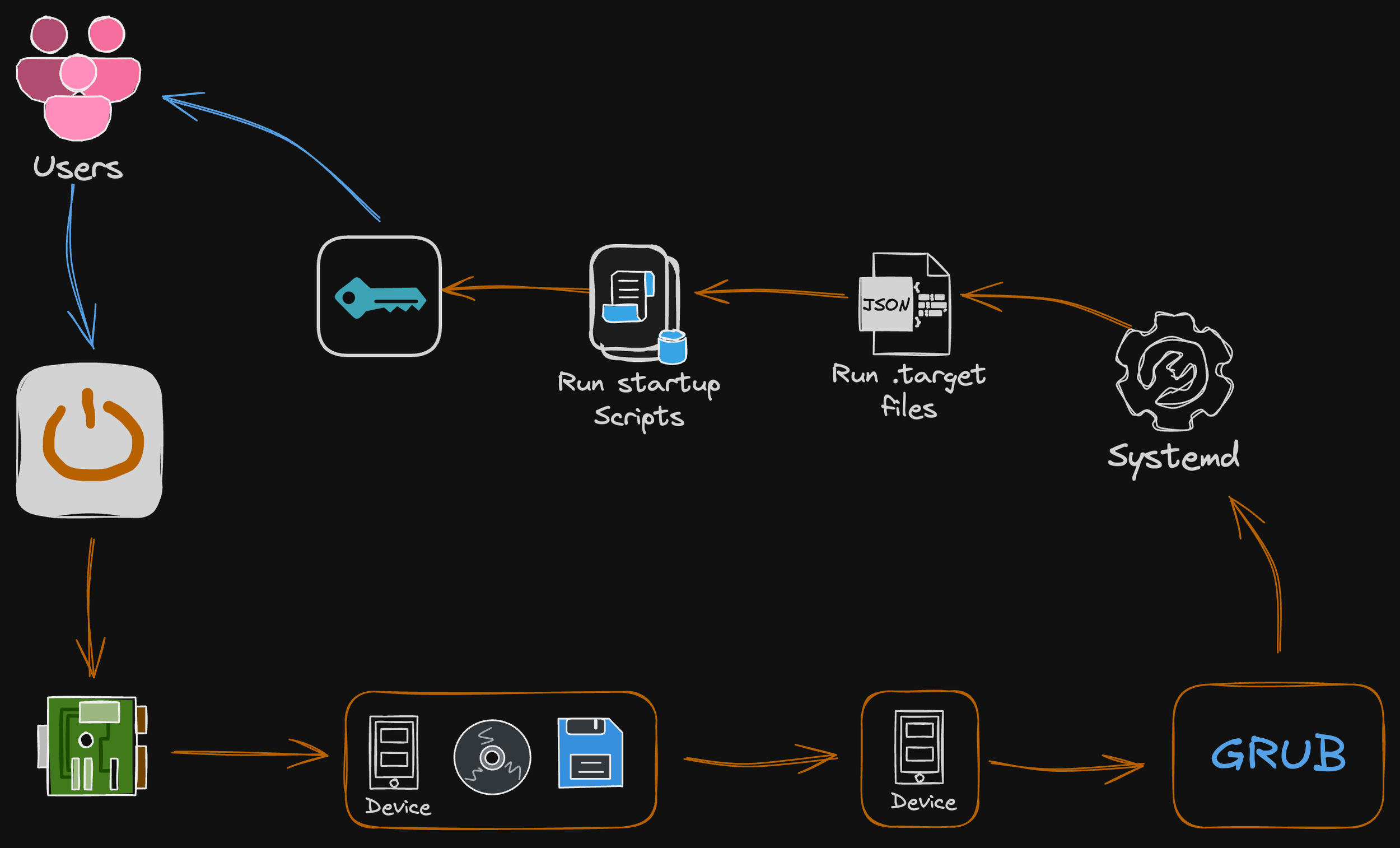

A High-Level View of the Linux Boot Process

Diagrammed below, you’ll find a high level overview of the Linux Boot Process, as explained in the previous sections. In a nutshell, the process includes the listed series of steps:

When a user powers Linux on, BIOS or UEFI firmware is loaded from non-volatile memory, and executes POST.

BIOS/UEFI detects the devices that are connected to the system, including CPU, RAM, and storage.

The system then chooses a booting device to boot the OS from. This can be the hard drive, the network server, or CD ROM.

BIOS/UEFI runs the boot loader (GRUB), which provides a menu to choose the OS or the kernel functions.

After the kernel is ready, we’ll now switch to the user space. The kernel starts up systemd as the first user-space process, which manages the processes and services, probes all remaining hardware, mounts filesystems, and runs a desktop environment.

Systemd then activates the default .target unit by default when the system boots. Other analysis units are executed as well.

The system runs a set of startup scripts and then configures the environment.

The users are presented with a login window for authentications. The system is now ready for administration or other development activities.

Understanding the series of steps enables all parties involved in troubleshooting critical system issues negatively impacting the customer experience through degraded services performance.

Sketch of the linux boot processes kickstarting with the pink “user” icon, following the orange arrow redirects!

Final Thoughts: The Importance of the Boot Process

The boot process is the essential sequence that transforms hardware into a functioning system, used by many developers, engineers, and architects. It establishes the foundation for reliability, security, and performance by initializing hardware, loading firmware, and bringing the operating environment online. Proper design and management of boot steps—firmware configuration, secure boot, bootloader integrity, and kernel initialization—reduce failure domains, enable recoverability, and protect systems from low-level attacks. For engineers and system architects, investing effort in transparent, verifiable, and well-documented boot procedures pays immediate dividends in uptime, maintainability, and trust. Prioritize clarity, automation, and security in boot engineering to ensure devices start correctly and stay resilient throughout their operational life.