Virtual Private Clouds & Layered Traffic Workflows: Low-Level Networking for Cloud Applications

Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) provides an isolated, virtualized network namespace inside a cloud provider’s fabric. At low level, a VPC is a collection of virtual routers, virtual switches, virtual NICs, and policy engines managed by the provider. It maps your logical address space and policy objects onto the provider’s underlay. Understanding VPC fundamentals requires treating it as a software-defined network. This network often includes control plane objects (route tables, ACLs, security groups), govern distributed dataplane components (hypervisor vSwitches, virtual routers, packet forwarding agents, tunnel endpoints).

Where an image helps: diagram of VPC logical components (subnets, route table, IGW/NAT, peering, endpoints).

Key low-level Considerations:

CIDR Selection and Aggregateability: choose blocks to minimize overlap with on-prem and partner networks used for peering or VPN.

Deterministic Routing: Understand how the cloud platform synthesizes routing (route tables, gateway attachments, propagated routes).

Control plane vs Data plane: Control plane APIs alter configuration; data plane behavior (encapsulation, NAT, forwarding) is what determines packet paths and transformation.

Encapsulation and Implementation Details: Many clouds implement VPC isolation via overlay encapsulation (VXLAN, GENEVE) or dedicated virtual routing with host-based forwarding. Understanding the provider’s chosen mechanism helps reason about MTU, fragmentation, and troubleshooting.

Addressing and Subnet Design

Proper addressing and subnet design within a Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) are critical for cloud-native applications because they establish the foundation for scalability, security, and efficient network operations; well-planned IP addressing avoids conflicts and supports predictable growth, subnet segmentation enables isolation of workloads and application tiers for principle-of-least-privilege enforcement, and appropriate CIDR sizing and route planning reduce wasted address space while simplifying service discovery and load balancing. Thoughtful subnet placement across availability zones enhances high availability and fault tolerance, and alignment with hybrid connectivity patterns (VPN/Direct Connect) prevents overlap and routing complexity. Additionally, integrating address management with automation and infrastructure-as-code ensures repeatable deployments, eases hybrid/multi-cloud expansions, and streamlines monitoring and troubleshooting, all of which materially improve reliability and operational agility for cloud-native systems.

Key low-level Considerations:

IP Addressing Model

Choose an addressing scheme that avoids collisions with on-prem or partner networks; prefer RFC1918 blocks sized to anticipated growth (for example, /16 for a large environment, /20–/24 for application-level subnets).

Use consistent prefix lengths per tier to simplify route aggregation and filtering. For example, management/infra /24, application frontend /24, app backend /23, database /26.

Consider secondary IPs for containers or multi-NIC VMs; cloud providers often support assigning multiple private IPs to a single virtual NIC for NAT, service IPs, or sidecar patterns.

Subnet Placement and AZ-awareness

Create subnets per availability zone (AZ) to maintain fault isolation and control AZ-local routing. Each subnet maps to a logical broadcast domain (no classic L2 broadcast across AZs in most clouds).

Align subnets with failure domains and service SLAs. For example, create a database subnet in three AZs with smaller CIDRs and an application subnet with larger CIDRs.

IP Assignment and Leases

Cloud DHCP/metadata services provide IP assignment. When considering lease behavior, some clouds keep IPs allocated to an instance for retention; while others release immediately on termination. This affects firewall state and route stability.

For ephemeral workloads (containers, FaaS), use pod/application-level IP management (CNI) with IPAM plugins to coordinate allocation from subnet ranges.

Address Planning for Overlay and Service Networks

Reserve separate, non-overlapping CIDRs for overlays (e.g., VXLAN, GRE) and for CNI-managed pod networks. For example, VPC: 10.0.0.0/16, VXLAN overlay: 172.20.0.0/16, pod network: 100.64.0.0/10 (avoid overlap with VPC).

Application Design Patterns for Cloud-Native Development

Why design patterns matter in cloud and VPC contexts

Reuse of proven solutions: Patterns encapsulate best practices for solving common architectural problems (e.g., service-to-service connectivity, secure resource boundaries, fault isolation), reducing design risk and development time.

Platform constraints and opportunities: VPCs provide network-level isolation and control; cloud-native platforms (Kubernetes, serverless, managed PaaS) introduce runtime, orchestration, and operational models that influence pattern selection.

Nonfunctional requirements: Patterns help achieve scalability, availability, security, observability, and cost control in ways that are repeatable and auditable.

Composability: Real-world systems require combinations of patterns (e.g., layered network segmentation + service mesh + CI/CD pipeline); understanding each pattern’s intent and trade-offs enables effective composition.

Key Design Patterns

Network & Perimeter Patterns

Intent: Define boundaries and control ingress/egress, protecting resources and services.

Typical constructs: Public/private subnets, NAT gateways, internet gateways, bastion hosts, VPN/Direct Connect, ingress controllers and API gateways.

Outcomes: Reduced attack surface, controlled access for users and services, separation of external vs internal traffic.

Segmentation & Isolation Patterns

Intent: Isolate workloads for security, compliance, or operational independence.

Typical constructs: Multiple VPCs, VPC peering or transit gateways, dedicated namespaces or clusters, tenant isolation models (shared, dedicated, hybrid).

Outcomes: Fault containment, tailored security controls, clearer blast radius boundaries.

Service Connectivity Patterns

Intent: Enable reliable, scalable communication between services across networks and runtime environments.

Typical constructs: Service mesh (mTLS, traffic routing), internal load balancers, DNS-based service discovery, message queues, API gateway proxies.

Outcomes: Observability for inter-service traffic, policy-driven routing, resilience through retries and circuit breakers.

Data Patterns

Intent: Handle storage, data access, replication, and lifecycle while meeting consistency and performance needs.

Typical constructs: Colocated vs centralized databases, read replicas, data sharding, cache-aside or write-through caching, object storage for large artifacts, VPC endpoints for private data access.

Outcomes: Predictable latency, resilience against failures, compliance-aligned data residency, and controlled egress.

Compute & Deployment Patterns

Intent: Choose runtime and deployment model to match workload characteristics.

Typical constructs: Virtual machines in autoscaling groups, containerized workloads on Kubernetes, serverless functions, managed platform services, blue/green and canary deployments.

Outcomes: Improved resource utilization, faster delivery cycles, capacity elasticity.

Observability & Operations Patterns

Intent: Provide monitoring, tracing, logging, and automated operational control.

Typical constructs: Centralized logging, distributed tracing, metric collection, alerting, health probes, automated remediation runbooks.

Outcomes: Faster incident detection and resolution, quantifiable SLAs, data-driven optimization.

Security & Identity Patterns

Intent: Control authentication, authorization, secrets handling, and workload identity.

Typical constructs: Least-privilege IAM roles, attribute-based access control, secrets management, workload identity federation, encryption in transit and at rest.

Outcomes: Minimized credential exposure, auditable access, and simplified cross-account/service access.

Resilience & Availability Patterns

Intent: Ensure continuity under partial failures and enable graceful degradation.

Typical constructs: Multi-AZ and multi-region deployments, active/active vs active/passive topologies, circuit breakers, bulkheads, retry/backoff strategies.

Outcomes: Reduced downtime, predictable failure modes, and maintainable recovery procedures.

Trade-offs and selection principles

Start with requirements: Security/compliance, latency, throughput, cost, operational maturity, deployment velocity, and team skills.

Prefer simplicity: Choose the least complex pattern that meets requirements; complexity increases operational overhead.

Evaluate coupling vs isolation: Tighter coupling can simplify development but increases blast radius; isolation reduces risk at the cost of duplication and integration complexity.

Consider ownership and observability: Patterns that obscure visibility (e.g., unmanaged cross-VPC tunnels) add operational risk—prefer managed primitives that integrate with telemetry.

Cost vs performance: High-availability and low-latency designs often increaseApplication Design Pattern Considerations

Network segmentation and isolation: Define clear VPC/subnet boundaries for trust zones (public, private, management) and map application tiers to those zones. Use security groups and network ACLs as first-line controls; minimize broad allow rules.

Least privilege and identity: Favor identity-based access (IAM roles, workload identities) over network-based trust. Ensure instances, containers, and serverless functions assume minimal required roles and rotate credentials via managed services.

Resilience and locality: Design for failure domains (AZs, regions). Place stateful components with low-latency needs in close network proximity; replicate across AZs or regions per RPO/RTO requirements.

Observability and telemetry: Build consistent logging, tracing, and metrics into services. Ensure network flow logs and VPC-level telemetry are integrated with application traces to diagnose cross-tier issues.

Secure service-to-service communication: Enforce mutual TLS or platform-native service identity for intra-VPC communications. Combine with egress controls and network policies to reduce lateral movement risk.

Scalability and auto-scaling boundaries: Define which components can scale horizontally (stateless tiers, stateless microservices) vs. which require vertical scaling. Ensure subnets and IP addressing plan support projected scaling.

Infrastructure as code and environment parity: Model VPCs, subnets, routing, and security groups with IaC to ensure consistent environments across dev/test/prod. Automate drift detection.

Cost and resource optimization: Map network egress, NAT, and cross-AZ traffic costs into architecture decisions (e.g., consolidate shared services, colocate high-chatter components).

Compliance and data residency: Use VPC and region placement to meet regulatory constraints. Apply encryption-in-transit and at-rest policies consistently.

Multi-Tier Applications

What is a multi-tier application?

A multi-tier application separates functionality into distinct layers (tiers) that communicate over a network. Common tiers include presentation (web/UI), application (business logic), and data (databases/storage). Each tier is designed to be independently developed, deployed, scaled, and secured.

Why multi-tier architecture?

Modularity: Tiers encapsulate responsibilities, reducing coupling and making maintenance and upgrades easier.

Scalability: Each tier can scale independently based on load patterns (e.g., add web servers without scaling the database).

Fault isolation: Failures in one tier can be contained, reducing systemic risk.

Security: Layered controls enable defense-in-depth, limiting exposure of sensitive systems (databases) to only necessary traffic sources.

How multi-tier apps map to VPCs

Virtual Private Clouds (VPCs) provide logically isolated network environments in cloud platforms. Within a VPC, you design subnets, routing, and security controls that reflect the tiers of your application.

Public subnet: Hosts internet-facing resources, typically the presentation tier (load balancers, public web servers). These subnets have routes to the internet via an internet gateway.

Private subnet: Hosts internal-facing resources such as application servers and API endpoints. These are not directly reachable from the internet and communicate with the presentation tier through internal load balancers or NAT/egress paths.

Data subnet / isolated subnet: Hosts databases, caches, and storage backends. Access is tightly restricted—only specific application-tier IPs, security groups, or service endpoints are permitted.

Cross-VPC designs: Larger architectures may split tiers across separate VPCs for isolation, compliance, or scaling. Inter-VPC connectivity uses VPC peering, transit gateways, or VPNs with carefully controlled route tables and security policies.

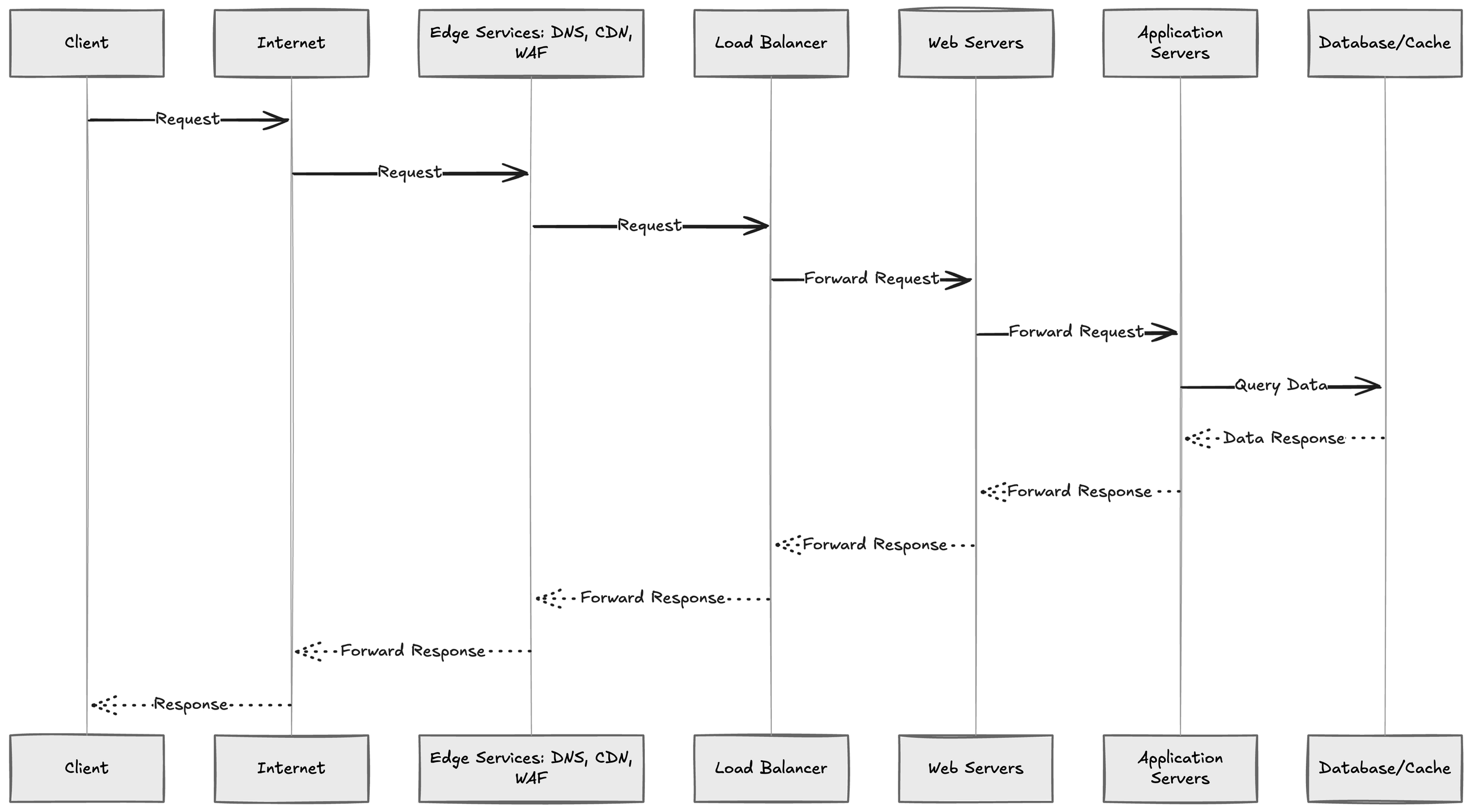

Layered traffic workflows

Typical request flow:

Client -> Internet -> Edge services: DNS, CDN, WAF

Edge -> Load Balancer in public subnet (presentation tier)

Load Balancer -> Web servers in public or private subnets (presentation)

Web servers -> Application servers in private subnets (application tier)

Application servers -> Database/cache in isolated subnets (data tier)

Responses propagate back along the same path to the client

Control points at each layer:

Network ACLs and route tables define permitted subnet-level traffic.

Security groups (stateful) control instance-to-instance and service-to-service traffic.

Internal load balancers manage distribution within the VPC and enforce health checks.

Service meshes or sidecars can provide fine-grained routing, observability, retries, and mTLS between services in the application tier.

API gateways consolidate north-south traffic control and authentication for microservices.

Design Considerations and Best Practices

Least privilege networking: Restrict access between tiers to only required ports, protocols, and source/destination ranges. Use security groups and network ACLs in combination.

Segmentation: Use multiple subnets and route tables to separate tiers and limit blast radius. Consider separate VPCs for high-sensitivity workloads.

Zero trust and strong identity: Prefer service identities (IAM roles, mutual TLS) over IP-based trust. Implement role-based access for management and automation.

Use private connectivity for data stores: Avoid exposing databases to the public internet; prefer private endpoints, internal load balancers, or service endpoints.

Observability and tracing: Instrument each tier for logs, metrics, and distributed tracing to debug cross-tier issues and measure performance.

Automation and immutable infrastructure: Automate VPC, subnet, and security provisioning through IaC (infrastructure as code). Use immutable images for tiers to simplify deployments and rollback.

Scalability patterns: Autoscale presentation and application tiers based on appropriate metrics (request rate, CPU, latency). Use read replicas, caching, and partitioning for database scale.

High availability and failover: Distribute tiers across multiple availability zones. For multi-VPC or multi-region deployments, plan routing, replication, and failover strategies.

Compliance and data residency: Place sensitive data in dedicated subnets/VPCs that satisfy regulatory controls and logging/monitoring requirements.

Common Pitfalls

Overly permissive security groups or overly broad CIDR rules that expose internal tiers.

Tight coupling between tiers (e.g., direct database access from many sources) that increases attack surface and maintenance complexity.

Insufficient observability across tier boundaries, making fault isolation difficult.

Relying on public IPs for inter-tier communication instead of internal endpoints, increasing latency and exposure.

Microservices and Service Meshes

Microservice architecture breaks a monolithic application into small, independently deployable services that each implement a single business capability. Services communicate over the network using lightweight protocols and are typically packaged and deployed independently. This modular approach improves scalability, maintainability, and fault isolation, but also introduces new challenges around service discovery, network security, observability, and traffic management.

Key characteristics of microservice-based applications

Decomposition: Functionality is split into narrowly scoped services (e.g., user, billing, inventory).

Independent lifecycle: Services can be developed, tested, deployed, scaled, and upgraded independently.

Network communication: Inter-service calls are frequent and must be efficient and reliable.

Infrastructure automation: CI/CD, containerization, orchestration (Kubernetes), and IaC are commonly used.

Resilience patterns: Circuit breakers, retries with backoff, timeouts, and bulkheads are important for fault containment.

Observability: Centralized logging, tracing, and metrics are essential to understand distributed behavior.

Why gRPC is commonly used in Microservices

gRPC is an RPC (remote procedure call) framework that uses HTTP/2 as its transport and protocol buffers for message serialization. It offers several advantages for microservices:

Performance: Binary serialization (protobuf) and HTTP/2 multiplexing reduce latency and bandwidth compared to text-based protocols.

Strong typing and contract-first development: Service and message definitions are specified in .proto files, enabling code generation for multiple languages and clear API contracts.

Streaming: Support for unary, server streaming, client streaming, and bidirectional streaming enables efficient handling of real-time, long-lived, or high-throughput interactions.

Interoperability: gRPC supports many languages and integrates with modern ecosystems.

Built-in features: Deadlines (timeouts), cancellation, and error codes are first-class, simplifying reliability patterns.

gRPC in VPC contexts

A Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) provides an isolated networking environment within a public cloud. Integrating gRPC-based microservices with VPCs typically involves the following considerations:

Network segmentation and isolation:

Place microservices in VPC subnets according to trust zones (public, private, management).

Use security groups and network ACLs to restrict which services or components can reach gRPC endpoints.

Service discovery and internal DNS:

Use VPC-native service discovery (e.g., cloud DNS, internal load balancers, or service mesh) to resolve services' addresses.

Ensure DNS TTLs and health checks align with expected failover behavior.

Load balancing and ingress:

Internal load balancers (L4/L7) or service mesh sidecars can distribute gRPC traffic. Because gRPC runs over HTTP/2, load balancers and proxies must support HTTP/2 correctly to preserve multiplexing and streaming features.

For external exposure, use edge proxies or API gateways that translate client protocols if needed and enforce authentication and rate limits.

Security:

Use mutual TLS (mTLS) to authenticate and encrypt gRPC calls within the VPC or between VPCs.

Leverage IAM and VPC-native controls for access to infrastructure resources.

Cross-VPC and hybrid connectivity:

Use VPC peering, transit gateways, or VPNs to enable gRPC calls across VPCs or between cloud and on-premises networks. Ensure MTU, routing, and firewall rules preserve HTTP/2 behavior.

Consider service mesh or secure proxies to handle authentication/authorization across trust boundaries.

Layered traffic workflows for microservices using gRPC A layered traffic workflow organizes how traffic moves from clients through a sequence of layers—edge, gateway, service mesh, and backend services—each adding capabilities like routing, security, observability, and resilience.

Typical Layered Flow:

Edge layer (Client → Edge Proxy / API Gateway)

Accepts client requests and performs authentication, TLS termination (if exposing external endpoints), and global routing.

Translates protocols if necessary (e.g., REST to gRPC or gRPC-Web).

Enforces rate limiting, WAF rules, and caching at the edge.

Gateway layer (API Gateway / Ingress Controller)

Provides VPC-aware ingress, ingress policies, and transforms requests into the internal service protocol (gRPC).

May perform coarse-grained routing to service clusters or versions (blue/green, canary).

Service mesh / sidecar layer

Each service instance runs a sidecar proxy (or uses platform proxies) that handles service-to-service mTLS, fine-grained routing, retries, circuit breaking, and telemetry.

The mesh centralizes policy (authorization, routing) and observibility. Microservice boundaries and granularity: Define services around business capabilities, balancing independence and operational overhead. Keep contracts (APIs, events) explicit and versioned.

Design Considerations

Service boundaries and domain modeling

Define services around bounded contexts and business capabilities, not technical layers. Use domain-driven design (DDD) to identify cohesive responsibilities.

Keep services small enough to be independently developed and deployed, but large enough to avoid excessive distributed complexity.

Consider data ownership: each service should own its data store to enforce autonomy.

API design and contracts

Design stable, versionable contracts (API-first approach). Use backward-compatible changes (additive fields) wherever possible.

Consider synchronous vs. asynchronous APIs. Use REST/gRPC for request/response interactions and messaging/event-driven APIs (Kafka, RabbitMQ) for decoupling and eventual consistency.

Provide clear, machine-readable specifications (OpenAPI, protobuf) and publish them to consumers.

Data management and consistency

Prefer eventual consistency for cross-service workflows; use sagas or choreography/orchestration patterns to manage distributed transactions.

Avoid distributed transactions (two-phase commit) except where absolutely necessary. Use compensating actions for rollback semantics.

Design for duplication: replicate read-optimized views or caches when necessary to reduce cross-service calls.

Communication patterns and reliability

Choose the right communication protocol per use case: low-latency RPC for internal calls, message buses for decoupling and resilience.

Implement retries with exponential backoff and jitter; guard against retry storms with circuit breakers and rate limiting.

Use idempotency for operations that may be retried to prevent duplicate effects.

Observability: logging, tracing, metrics

Centralize logging and use structured logs to connect traces across services.

Implement distributed tracing (OpenTelemetry) to track request flows and measure latency across service boundaries.

Define and monitor service-level metrics (latency, error rates, throughput) and business metrics. Set meaningful alerts and SLOs/SLIs.

Resilience and fault isolation

Design for failure: use bulkheads to isolate resources (threadpools, connection pools) per downstream dependency.

Implement circuit breakers, timeouts, and graceful degradation to avoid cascading failures.

Ensure services can fail fast and recover quickly (stateless services are easier to scale and recover).

Deployment and CI/CD

Automate builds, tests, deployments, and rollbacks. Use pipelines that test both individual services and integration/end-to-end flows.

Adopt containerization and orchestration (containers, Kubernetes) to manage lifecycle, scaling, and placement.

Use feature flags to gradually introduce changes and enable dark launches.

Security and compliance

Secure service-to-service communication (mTLS) and enforce authentication and authorization (OAuth2, JWT, or API gateway policies).

Apply the principle of least privilege for network, IAM, and data access. Encrypt data at rest and in transit.

Consider compliance and data residency: design services to minimize scope of regulated data and simplify auditing.

Operational considerations: scaling, cost, and manageability

Design services to scale independently; partition state and use stateless service patterns when possible.

Monitor operation costs (compute, storage, network). Avoid excessive cross-service chattiness that increases latency and costs.

Standardize tooling and runtime libraries to reduce cognitive load and operational variance.

Common Pitfalls

Poorly defined service boundaries

Splitting by technical layers (UI, DB per service) or splitting too narrowly leads to chatty, brittle systems and distributed monoliths.

Overly large services recreate monoliths and negate benefits of microservices.

Tight coupling between services

Direct synchronous coupling on critical paths results in cascading failures and brittle deployments. Over-reliance on tight coupling prevents independent releases.

Sharing databases across services or using shared ORM models creates hidden dependencies.

Ignoring operational complexity

Underestimating the operational overhead (monitoring, deployment, testing) of many services leads to fragile systems.

Not investing in observability makes diagnosing problems slow and error-prone.

Inadequate testing strategies

Relying only on unit tests; failing to implement contract tests, integration tests, and end-to-end tests leads to runtime failures.

Not automating test environments that mirror production behavior (messaging, latency, failures).

Insufficient attention to data consistency

Attempting synchronous consistency across services without proper patterns causes latency and availability problems.

Failing to handle eventual consistency in client logic (stale reads, out-of-order events) introduces bugs.

Poor error handling and retry policies

Blind retries without idempotency or backoff cause duplicate processing and overload services.

Lack of timeouts can cause resource

Call to Action

A.M. Tech Consulting delivers innovative engineering and technology services tailored to advance your projects from concept to reality; our experienced team combines practical engineering expertise, cutting-edge technology solutions, and a client-focused approach to design, develop, and optimize your next big idea. Contact A.M. Tech Consulting today to discuss your project and learn how we can create a custom solution that meets your goals—partner with us for the best chance to bring your vision to life!